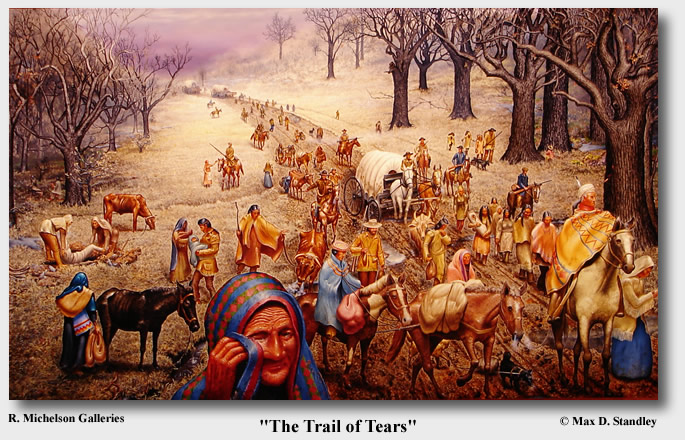

Removal of Cherokee Indians and others to Oklahoma.

Nunna daul Tsuny — “The Trail Where They Cried”

On January 10, 1806, President Thomas Jefferson addressed a gathering in front of the White House in Washington, D.C. The occasion — a concluding ceremony following a series of meetings with the chiefs of the Cherokee Indian Nation, and others, who had been invited to Washington as a gesture of friendship.

On January 10, 1806, President Thomas Jefferson addressed a gathering in front of the White House in Washington, D.C. The occasion — a concluding ceremony following a series of meetings with the chiefs of the Cherokee Indian Nation, and others, who had been invited to Washington as a gesture of friendship.

Jefferson opened with:

“My friends and children, chiefly of the Cherokee Nation,

“Having now finished our business an to mutual satisfaction, I cannot take leave of you without expressing the satisfaction I have received from your visit. I see with my own eyes that the endeavors we have been making to encourage and lead you in the way of improving your situation have not been unsuccessful; it has been like grain sown in good ground, producing abundantly. You are becoming farmers, learning the use of the plough and the hoe, enclosing your grounds and employing that labor in their cultivation which you formerly employed in hunting and in war; and I see handsome specimens of cotton cloth raised, spun and wove by yourselves. You are also raising cattle and hogs for your food, and horses to assist your labors. Go on, my children, in the same way and be assured the further you advance in it the happier and more respectable you will be.”

Such repugnant, condescending, and patronizing language is no longer used by civilized people nor politicians. But even though attitudes have changed over the past 200 years Native Americans are still treated like children by the federal government through policies carried out by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Department of Interior. Treaties were ignored in 1806 and they are ignored today.

Jefferson went on to say:

“Our brethren, whom you have happened to meet here from the West and Northwest, have enabled you to compare your situation now with what it was formerly. They also make the comparison, and they see how far you are ahead of them, and seeing what you are they are encouraged to do as you have done. You will find your next want to be mills to grind your corn, which by relieving your women from the loss of time in beating it into meal, will enable them to spin and weave more. When a man has enclosed and improved his farm, builds a good house on it and raised plentiful stocks of animals, he will wish when he dies that these things shall go to his wife and children, whom he loves more than he does his other relations, and for whom he will work with pleasure during his life. You will, therefore, find it necessary to establish laws for this. When a man has property, earned by his own labor, he will not like to see another come and take it from him because he happens to be stronger, or else to defend it by spilling blood. You will find it necessary then to appoint good men, as judges, to decide contests between man and man, according to reason and to the rules you shall establish. If you wish to be aided by our counsel and experience in these things we shall always be ready to assist you with our advice.”

Seven treaties with the Cherokee later, the United States, “because he happens to be stronger,” took all Cherokee land East of the Mississippi River. In exchange the Cherokee were given $5 million and an Indian Reservation in Oklahoma Territory. Of course, the Cherokee were never handed $5 million. That’s the amount that was to be spent on their behalf, for public facilities and “mills to grind your corn.”

The treaty that put the move in motion was the Treaty of New Echota, signed at Echota, Georgia, on Dec. 29, 1835. Two and a half years later the relocation plan went into effect with legal authority provided by the U.S. Congress. In 1830 Congress had passed the Indian Removal Act although many Americans were against the concept, most notably Tennessee Congressman Davy Crockett.

But President Andrew Jackson quickly signed the bill into law.

However, the treaty required ratification by the Senate and there was strong opposition, but it passed by a single vote. Among those speaking out against ratification were Daniel Webster and Henry Clay.

In one of the saddest episodes of our brief history, men, women, and children were taken from their land, herded into makeshift forts with minimal facilities and food, then forced to march a thousand miles. Under the general indifference of army commanders, human losses and suffering was extremely high.

The Routes to Oklahoma

The first three detachments of Cherokee left by water in June, 1838. Those groups left under military supervision, before the Cherokee asked for and were granted permission to supervise their own migration. River routes were followed Northwest from Northern Georgia and Western North Carolina/East Tennessee to the Mississippi, then South down the Mississippi to the mouths of rivers from the West, to Oklahoma.

Twenty-eight hundred Cherokee were divided into three detachments, each accompanied by a military officer, a corps of assistants, and two physicians. The first group with about 800 in the party departed June 6, with the other two detachments starting after the fifteenth of June. Those detachments traveled water routes and are thought to have experienced a much higher rate of deaths and desertions than those who followed later overland.

It’s a myth that the relocation was only Cherokee. It included the Seminole of Florida, the Choctaws from Mississippi and Alabama, the Creeks from South Georgia, and others.

Trail of Tears Timeline — 1838

- February: 15,665 people of the Cherokee Nation petition congress protesting the Treaty of New Echota.

- March: Outraged American citizens throughout the country petition congress on behalf of the Cherokee.

- April: Congress tables petitions protesting Cherokee removal. Federal troops ordered to prepare for roundup.

- May: Cherokee roundup begins May 23, 1838. Southeast suffers worst drought in recorded history. Leader Tsali escapes roundup and returns to North Carolina.

- June: First group of Cherokees driven west under Federal guard. Further removal aborted because of drought and “sickly season.”

- July: Over 13,000 Cherokees imprisoned in military stockades awaiting break in drought. Approximately 1500 die in confinement.

- August: In Aquohee stockade Cherokee chiefs meet in council, reaffirming the sovereignty of the Cherokee Nation. John Ross becomes superintendent of the removal.

- September: Drought breaks — Cherokee prepare to embark on forced exodus to Indian Territory in Oklahoma. Ross wins additional funds for food and clothing.

- October: For most Cherokee, the “Trail of Tears” begins.

- November: Thirteen contingents of Cherokee cross Tennessee, Kentucky and Illinois. First groups reach the Mississippi River, where their crossing is held up by river ice floes.

- December: Contingent led by Chief Jesse Bushyhead camps near present day Trail of Tears Park located near Cape Girardeau, Missouri. John Ross leaves Cherokee homeland with last group, carrying the records and laws of the Cherokee Nation. 5000 Cherokees trapped east of the Mississippi by harsh winter — many die.

Trail of Tears — 1839

- January: First overland contingents arrives at Fort Gibson. Ross party of sick and infirm travel from Kentucky by river boat.

- February: Chief Ross’s wife, Quati, dies near Little Rock, Arkansas on February 1.

- March: Last group headed by Ross, reaches Oklahoma. More than 3000 Cherokee die on Trail of Tears, 1600 in stockades and about the same number en route. 800 more die in Oklahoma in 1839.

- April: Cherokees build houses, clear land, plant and begin to rebuild their nation.

- May: Western Cherokee invite new arrivals to meet to establish a united Cherokee government.

- June: Old Treaty Party leaders attempt to foil reunification negotiations between Ross and Sequoyah. Treaty Party leaders, Major John Ridge and Elias Boudinot, assassinated.

- July: Cherokee Act of Union brings together the eastern and western Cherokee Nations on July 12, 1839.

- August: Stand Watie, Brother of Boudinot, pledges revenge for deaths of party leaders.

- September: Cherokee constitution adopted on September 6, 1839. Tahlequah established as capital of the Cherokee Nation.

Treaties signed over fifty year span:

|

Treaties signed with the Cherokee |

|

| Hopewell |

Nov 28, 1785 |

| Holston |

Jul 02, 1791 |

| Philadelphia |

Feb 17, 1792 |

| Philadelphia |

Jun 26, 1794 |

| Tellico |

Oct 24, 1804 |

| Tellico |

Oct 25, 1805 |

| Tellico |

Oct 27, 1805 |

| Washington |

Mar 22, 1816 |

| Chickasaw Council House |

Sep 14, 1816 |

| Cherokee Agency |

Jul 08, 1817 |

| Washington |

Feb 27, 1819 |

| Washington |

May 06, 1828 |

| Washington |

Mar 14, 1835 |

| New Echota |

Dec 29, 1835 |